JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

Harvest and home

Autumn swept into Melbourne last week with one last, brutal heatwave, scorching gardens and people alike, and reminding us that our place on this brown and sunburned land is insubstantial. In my family, the threads that tie us to this landscape are gossamer, only two generations young, and our biology has not caught up with our climate. Every time the mercury rises we are driven inside, hiding from the weather in the relative cool of double-brick walls and high ceilings and air conditioning.

Autumn is harvest time, usually a season of delicious bounty, but heatwaves here and drought there and floods over there have left many of my country’s crops rotting, or burned away, or not even planted. Often we are insulated from these events in the city, the travails of the farmers and producers only an hour or two away from us go unnoticed amid bulk discount produce in the supermarket, shipped in on ice from many thousands of kilometres away. But when a head of broccoli soars to $10.75 a kilo, surely more people will start to take notice.

We do our best to buy locally, supporting our farmers or the high-street shops that in turn support the farmers, and we follow the seasons as best we can, buying our food when it is at its best and was picked just the other day and just around the corner (rather than last month and in another time zone).

But if you can’t grow the crops yourself, it’s not always easy to know what is at its best, when.

This was easier in France. Shopping at the farmers’ markets in Dinan every week, I tried to let the produce inspire my cooking, rather than carrying a shopping list with me (I wrote about that in my newsletter last month, and you can read it here if you’d like to).

I quickly learned from this experience how ill-equipped I was as a cook to plan our meals in this way, and scouted around for some kind of guide to help me. And, this being France, naturally I found one. It was a little book called “Agenda Gourmand: use année de recites avec des produits de saison” (which is fairly self-explanatory even if you don’t speak French, but roughly means “Food planner: yearly recipes with seasonal produce”). There was a week to each opening, celebrating the produce that was likely to be at its best on that particular week, and sharing recipes and other tips for using and cooking with them.

Back in Melbourne now, I have decided to create - and paint - an agenda gourmand of my own, noting down the best times to plant, harvest, buy and forage for food where I live, and collecting my favourite recipes, remedies and stories for making use of them. I hope it will become my go-to food guide for seasonal eating, and maybe something I can pass down to my children as well.

I also hope it will become a celebration of the beauty and abundance of nature, both in paint and in words. Another way for me to make peace with my country, even when the heatwaves are relentless and fierce.

So I have started painting, and I have started reminiscing…

Pears…

They were never my favourite. Too sweet, too juicy, and with that funny, fuzzy texture on the tongue… not for me. (Although hard to surpass in a rocket salad with parmesan cheese and rocket, it’s true, to complement the pork ragu I like to make in autumn).

And then there was that tarte au poire I ate atop the Eiffel Tower in the autumn of 2011, on the holiday from which, unknowing at the time, I would bring my daughter home inside me.

September was cooling down. It had been raining, and parts of the metal steps were slippery as I climbed, alongside two friends I’d known and loved since childhood. I’d been to Paris before but this was my first time climbing the tower, and no amount of cliché, nor the blisters from the new red ballet-flats I’d mistakenly thought would be romantic on a visit to Paris, could make the moment less magical.

At the top we bought hot chocolates, and my friend Lindy chose a pear tart for us to share. It was one of those moments. Paris in the rain. The Eiffel Tower. Beloved friends… and that tart. Sweet, vanilla pastry, a hint of almonds, and juicy pears (fresh, with the skin still on them) arranged in a beautiful flower and glowing under a delicate glaze.

That was the day I made friends with pears.

Radishes…

Sharp and clean, with a pepper-like crunch that warms a winter salad and makes orange sing. Slice them thinly, then hold the slices up to a window to see them glow like tiny moons.

Radishes are the first vegetable I remember growing. My mother found us a little patch of dirt around the side of our suburban house in Berowra Heights, and told us we could grow our very own vegetables. She told me she chose radishes because they were so easy to grow, even in cooler weather, and they were relatively quick: you have to harvest radishes early or they become hot and spongy.

I remember the touch of the warm soil as I drew a line in my little vegetable patch with my finger, carving a trench just deep enough to carefully place the seeds along the line I’d made, each of them two hands apart, before covering and gently patting the soil smooth again. The staggering weight of the watering can as I tilted it over my future harvest, barely able to hold it up. And the excitement when the first, green shoots poked up through that carefully tended soil… And then the waiting - oh! the waiting! - with the sublime impatience of childhood, for the harvest day to come.

Something else I remember: the extraordinary underwhelm of my first bite. Pepper! I suspect I wailed, “Too hot!” The flavour that now brings me so much delight (is there anything better, paired with pomegranate seeds, watercress, honey and fresh mint?) was a resounding failure in my childhood vegetable patch. I don’t remember what came next. Carrots, maybe?

Apples…

The apple tree at the front of our house is fruiting this year. It’s just a crabapple tree, nothing we can pick and munch for morning tea like the gala apple I’ve painted here (I had to label it in the ‘fridge: “Mummy’s art, don’t eat.”) I chose the crabapple for our tiny front yard because the blossom trees on the next street over were so spectacular that in spring they would take your breath away. I think you could see those rows of blossoms from space, and that’s something special in the inner city. I love these trees so much I contacted the chief arborist at our local council to find out exactly what variety they were, so I could have my very own piece of blossom heaven.

I missed the blooms on our tree last year, because we were in France, but my husband tells me they were every bit as glorious as I’d hoped. And now our little tree is fruiting. Every morning as the children and I set off on our walk to school, we say hello to our tree and inspect the baby fruit, which seems simultaneously so improbable and yet so lovely in our tiny city yard.

In Dinan, there was a public apple orchard. Mostly cider apples, growing wild and unharvested on the side of the hill beneath the castle walls. There was a path winding through the apple-trees down to the river (they called the path a ‘Chemin des Pommiers’ - an apple walk), so covered in fallen apples in October that a gentle stroll became a slippery and treacherous clamber. But the air inside the orchard was perfumed with apple-flavoured honey.

Also this podcast about apple trees, with Lindsay Cameron Wilson, makes me so happy.

What are your stories?

Midwinter mystery

I wanted to watch the sun rise through the standing stones on the winter solstice.

In truth, the true magic was supposed to happen at sunset: the last of the day’s light beaming through the passageways of the southwest-facing cairns and spilling over the ancient dead like a gift, for a few precious moments in this one important hour every year, for four thousand years.

But sunset in mid December was at 3.30 in the afternoon, and I knew we’d probably still be out. We had made plans to visit a tiny village close to Nairn, and walk ten kilometres though fields to see Cawdor Castle in the distance, the seat of my distant Calder relatives. Probably, I thought, we’d still be driving home at sunset. (We were).

And the forecast was for rain in the afternoon, anyway.

So we hurried down our breakfast and left in the dark, arriving just in time to watch the dawn instead, as it coloured the ancient wood in gold, and sent the fairies shimmering back into the shadows, seconds before the sun’s rays broke then burst over the nearby hills.

My family wandered with me for a few minutes but then retreated to the relative warmth of the car, leaving me to explore the cairns and stones alone.

For a little while, I pulled my gloves off and rested my fingertips on the ancient standing stones, letting the earth’s currents flow up through that quiet ground and the lichen-covered stone, then coursing into my hands and grounding my body in nature and history.

Four thousand years. It’s an almost unthinkable age to me but, to our planet, those stones are little more than the passing acne of adolescence on the surface of time.

The stones were sharp with ice, and smooth inside the “cups,” little circular dips carved out with stone or antler tools, patiently worked by human hands millennia ago. Hands just like mine, maybe even genetically related to mine, but on people leading lives so different to my experience it is impossible to fathom that which binds us.

Except this earth. This dawn. These stones. They are our constant, linking me to them and them to me as though time did not matter and they had just - just - left, melting away into shadows with the fairies mere moments before I arrived with the sun.

Who were they?

These ancient ancestors of ours positioned the cairns to catch the solstice sunset, and graded the standing stones around them according to astronomical axes. Those that face the sunrise are smaller and whiter, while those placed toward the sunset are larger and the lichen, when scraped away, reveals stones of pink and red.

Artists of the earth.

While I stood alone and watched, the morning sun pierced a cleft stone in the lonely field.

On a whim, I stepped behind the stone and let the cut-light pierce and refract over my face, closing my eyes to the gold, and turning it red beneath my lids.

What do you think it means, that split stone? It is not the biggest nor the most impressive of the standing stones that guard these cairns, but the cleft feels strange, not something you see in nature, and to me it feels like a question. Two almost identical pieces of stone, side by side, kissing at the base but pushing one another apart at the shoulders, creating unearthly shadows and bending the sun’s rays and creating a hard-to-pin-down sense of unease.

Like listening to your parents argue in the next room.

Our humanity unites us throughout the millennia. These stones are part of me and I am part of them. But what do they mean?

Lessons from the summer garden

I have been waiting for the weather to cool.

The summer’s evening we returned home from France, I stood in my little garden in the shocking humidity, and took these pictures. It was a jungle. Abundant and overgrown, some plants thriving and other plants choking, and I made plans to gently nurture it back to life. My very own Secret Garden.

I made a start, cutting back the valerian and unwinding the clematis so the other plants could breathe. There was no saving the blueberry bush, one of the hydrangeas or two of the camellias. Two out of three of the Japanese maples were looking decidedly sad.

But I still held out hope for the roses, the pomegranate, and my favourite oak-leaf hydrangea, and the honeysuckle was so healthy it had all-but swallowed the children’s cubby house whole.

But instead of making it better, I only made things worse. Clearing away the overgrown vines left my space-starved plants vulnerable when the heat came - and come it did, less than a week later, in waves of day after day with temperatures in the late 30s and early 40s, Celsius.

No amount of water can keep alive a plant that is being literally burned from the sky. One of my happily-blooming fuchsias was the first to go. At the end of one particularly long, hot day (long after dark it was still 36 degrees), every leaf had turned brown. When I cupped the leaves in my hand, they fell from the stems and crumbled to dust.

The little Jack Frost plants soon followed suit, and most of the Japanese windflowers. Soon my gardenias were looking sad, the oak-leaf hydrangea crisped at all the edges, and the leaves began dropping off the Japanese maple.

None of the border plants survived, and brown began to swallow green.

The poets of ancient Jerusalem wrote, “To everything there is a season.” (Or were they quoting Pete Seeger?) And nowhere is that more evident than in an actual garden, where the seasons govern, and human intervention can only go so far in changing or mitigating what nature intends.

One of the things I noticed about the public flower gardens in France was that in spring and summer, they were more beautiful than anything you could imagine: full of shocking, extravagant colour like a fragrant, bee-filled rainbow explosion. But when autumn came and the seed-heads drooped, gardeners cut everything back, aerated the ground, and let it rest for the cooler months. It wasn’t pretty: brown patches of earth with the odd leftover strand of sad annual eking out the last of its days.

We don’t tend to do that in Australia. We plant and tend for year-round cover, and seek colour in every season. I know I’ve tried this in my own little garden, filling those brown patches as best I can in winter so we only look out on green.

But respecting the season means working with nature, rather than fighting it.

Those plants in my garden shouldn’t have been left to smother one another but, once it was done, I should have known better than to strip things bare right when the worst of the heat was about to begin. And I had known it would begin: January and February where I live are the hottest months of the year.

But I was impatient, eager to reconnect with my home by putting my hands in the earth, and I wouldn’t wait. In many parts of Europe, brown and grey are the colours of winter. I made them the colour of Melbourne in summer, too.

Gardens teach us patience, if we will let them. To everything there is a season. There is a season for brown, and a season for colour. A season for hot, and a season for cold.

A season for abundance, and a season for rest.

My friend Brenner and I send one another voice-messages most days, little audio missives that carry with them the ambience of our respective worlds. In mine, while soaring temperatures burn everything around me and sting my eyelashes, there is a heartbreaking crunch of dry things underfoot as I walk and talk. In Brenner’s messages, sent to me from her home in tropical far-north Queensland, I hear frogs and cicadas, and the soft and ever-present sound of rain. Up there, these seasons aren’t spring-summer-autumn-winter. They are known as the wet season, and the dry.

Nature comes back.

Even my burnt plants will re-shoot leaves. And if they don’t, others will clamber over and take their place.

So I will wait. When the weather cools, I will replant but, when winter comes, I will allow my garden to rest. To lie fallow, the way nature intended. It’s ok, I will remind it, to be brown.

Come spring, I hope I can bring you a rainbow.

Ten days of illustrations

I’m just past 10 days into the #100DaysinDinan project, and so far I am loving it! As I had hoped, taking out the time to draw these pictures each day is taking me back to our time in the village, and how it has influenced me and my family in big ways and small.

To jog my memory and find things to paint, I’ve been scrolling through photos in my camera, and that has been an extra-welcome trip down memory lane. The children love to see what I’ve been painting each day, often chiming in with “Remember when…?” as they hold the little cards in their hands.

I’m making the envelopes for each card by tracing one of the original envelopes the cards came in, onto used calendars and magazine pages. A stamp or two, and the address: there’s not much room for anything else, so into the post they go.

Here are the first 10 that I’ve painted and posted, with a bit of the back-story behind them.

hotel de beaumanoir

The beautiful, 15th-century archway to the former hotel de Beaumanoir: 1 rue Haute-Voie, Dinan. This was just around the corner from our apartment and after dropping off our bags on Day 1, we took a wander through town. This intricate stone archway took my breath away, and I couldn’t believe I was going to live in such a place

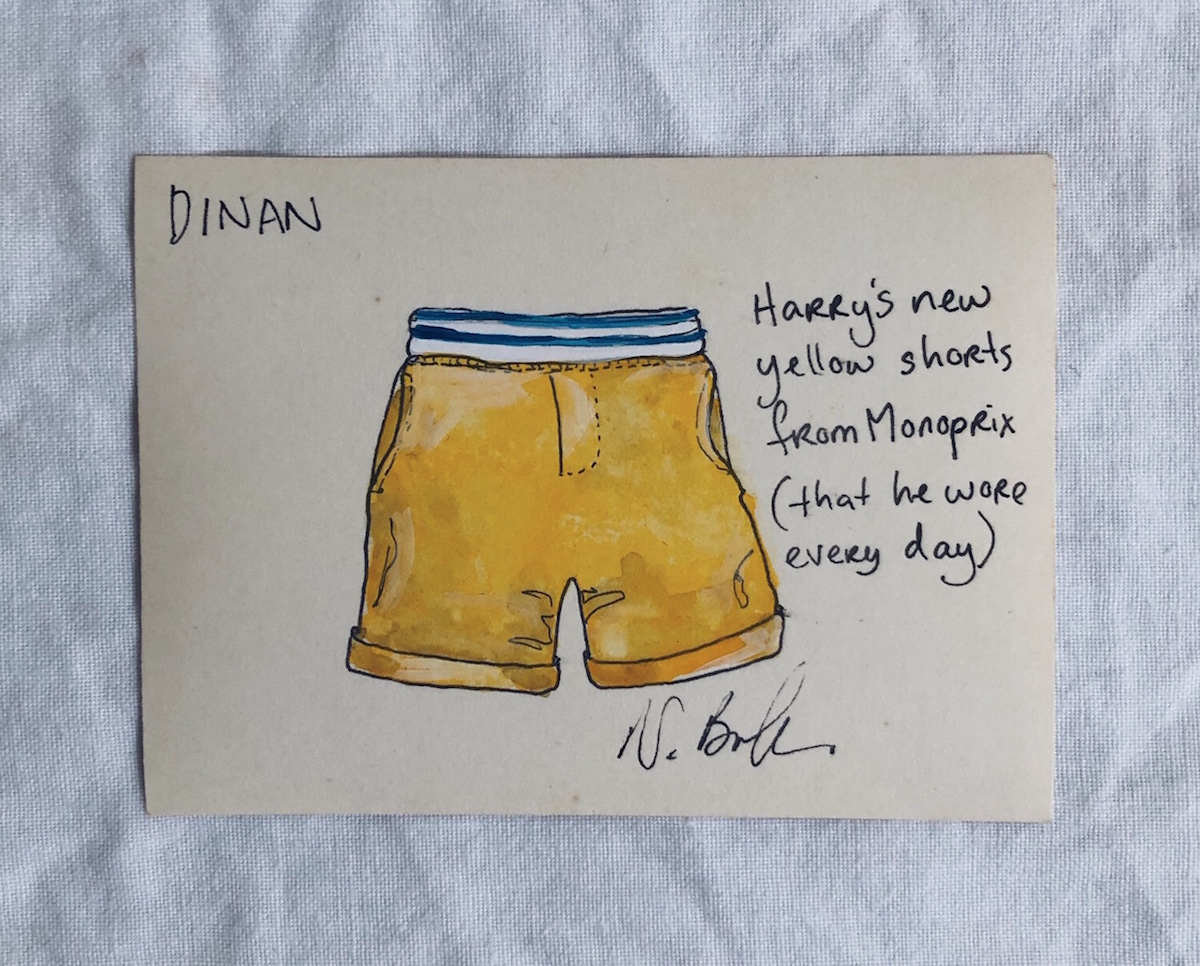

new yellow shorts

We arrived in France from the coldest month of winter in Australia, with very few summer clothes in the suitcase as the children had already grown out of theirs from six months earlier. While riding the carousel in the hot sun the day after our arrival, four-year-old Ralph found his jeans just - too - hot. I popped into the Monoprix and bought him these sweet yellow shorts, which he loved so much that he wore them nearly every day until the end of summer

maison bazille

There are several chocolatiers in Dinan, and we sampled them all! Our favourite was Maison Bazille on 10 Rue de l'Apport. Partly for the silky homemade chocolate (made on the premises) with all kinds of flavoured ganache, and partly for the macarons, but mostly because Anne, the proprietress, was just so lovely. She would welcome us with beaming smiles, and when we returned after three weeks in the UK, she gave the children cuddles and kisses. We would slow down every time we walked past, in order to catch her eye and wave

half-timbered houses

Dinan is famous in France for the half-timbered houses that line its streets. They are crooked and wonky, because when they were built (mostly the 14th and 15th Centuries) there was a tax on floor-space at the ground floor, so people built small at the base and increasingly spread out as they built up. (This particular house is now a restaurant, La Mere Pourcel on 3 Place des Merciers. I really wanted to eat there but it looked too fancy for a mum and two kids, so I’ll have to go next time!)

moules-frites marinieres

Ralph was gung-ho with the moules-frites from the very beginning, but Scout only discovered them during a visit to Mont Saint-Michel. It was a steaming hot day, and we sheltered from the sun in a restaurant for lunch. I’d ordered myself a bowl of moules-frites while the children had pizza, but Scout ended up stealing more than three-quarters of my mussels. We told the proprietress they were the best we’d ever tasted, and she smiled and shrugged, “c’est la saison” (it’s the season)

rampart towers

There are lovely little towers in the castle walls all the way around Dinan. This one is over one of the steep streets that lead between the hilltop part of the town, and the ancient river port. The children and I would walk along the ramparts on the way home from school, and stop to take in the view from the top of this tower

the padlock letterbox

The steep, cobblestoned rue du petit fort leads all the way down to the river at Dinan, and the whole way down the little street is lined with ancient and fascinating homes, shops and cafes. This door is almost at the bottom, and boasts the biggest padlock you have ever seen, which now does duty as a private letterbox

sea-birds

Dinan doesn’t feel like a seaside town. There is a river, to be sure, but it no longer dominates the landscape or trade, ever since the town moved up the hill and behind the castle walls for safety, many hundreds of years ago. But this is the west coast of Brittany, and the sea is still close enough that sea-birds call and circle in the morning, and wander through the streets hoping for scraps from tourists at lunch

boats on the canal

The river Rance, by the time it gets to Dinan, is little more than a canal. The first week we arrived, we took a ride on a river-boat up the canal to the neighbouring town of Lehon, the children fascinated when we had to stop at a lock and wait for the water to rise. There was a path beside the canal where horses used to walk and pull the boats. Once, a family’s horse sadly died, so the captain’s wife had to ‘harness up’ and pull the boat herself. There are photos. In the summer, weekender boats like this one I’ve painted would chug past and we’d wave at them

birkenstock kilometres

The day before we left on our adventure, we took the children to the Birkenstock store in Melbourne and picked up a pair of sandals each. It was winter here in Australia, and they had long grown-out of their sandals from the previous summer. When we arrived in France, those sandals became synonymous with the new sense of adventure and resilience my children developed. From complaining about a two-block walk in Australia, they cheerfully walked 10+ kilometres every day in those sandals

The wuthering north

We drove into Cumbria after dark, just as the winds were picking up. Outside it was right on zero degrees, although the little weather app on my iPhone said, helpfully, “feels like -6”. It did.

The journey had been almost twice as long as we’d anticipated, an unlucky accumulation of London traffic that had continued for three hours outside London; a sun that set at half-past-three in the afternoon, leaving us to navigate our oversized hire-car through steep and winding country roads after dark; and, speaking of navigation, numerous opportunities to take wrong turns and get lost, which we did (there were even road-signs saying “don’t trust the sat-nav”).

From bed that night I could just see the soft, watery light of the crescent moon behind the still-gathering clouds, filtering and refracting through diamond-paned windows that had filtered and refracted moonlight into this room for 500 years, exaggerating the shadows of the beams in our ceiling. The wind was picking up, battering around the ancient walls of our gatehouse in a beautiful fury.

“I love it here,” I whispered to my husband, although he might already have been asleep. “I can’t even tell you. I really love it here!”

The moon was long gone by morning, and the sun was doing its best job of hiding, too, but the grey dawn revealed bare trees and stone walls and crumbling ruins and bracken-covered hills as far as the eye could see. I ran outside in my slippers, hugging my pyjamas close, and drew in the wild view like oxygen.

Back inside, I put on the kettle and made eggs on toast for my family, while the wind positively howled. “Wow!” said the children (about the weather, not my eggs). And as we sat down at the farmhouse table under a window, beside a cast-iron fire that was cracking and popping and spreading warmth, I thought, “We are inside Wuthering Heights.”

Naturally, there was a pretty village nearby, where one could find welcoming locals with musical accents and a cafe with cockle-warming, home-cooked meals. Also naturally, there was a castle ruin, a 900-year-old edifice on an ancient mound that was once settled by Danes and was still part of Scotland until a thousand years ago or so.

I climbed the hill to the ruins alone, while the rest of my family went to find somewhere to buy groceries. The promised “ice rain” had begun, and I have honestly never felt as cold as I did atop that wild and windswept hill, not even on the January night I walked home beside the Hudson River in New York with my friend, and we learned later that it had been -18 degrees.

It was the wind. The wind that burned my ears with cold like razors, stung my eyes with dry tears, tipped me sideways, and genuinely sucked the breath from my lungs whenever I faced into it. Literally breathtaking.

How is it that this world is so full of so many beautiful places? How can we bear it, in our hearts? We only stayed in this ancient gatehouse, perched on the edge of lovely emptiness, for two nights, but I cried for the beauty of it all three times.

I didn’t want to leave. But then, that’s also how I’d felt when first we climbed the steep, cobblestoned streets of Dinan, when we made our picnic under the trees at the castle ruins of Lehon, when we lay down in sunshine among fields of wildflowers in the grounds of Hever Castle, and when we lost ourselves inside the ancient, golden-hued forest of Broceliande. I know I’ve talked about this on my blog before, the twin concepts of home and belonging.

When I married my husband, we made the song Home is wherever I’m with you by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes the unofficial theme-song of our marriage, a testament to where we’d been and where we were going, after I’d left New York to live with him. Every time we moved to a new city, I sought out ways to make it feel like home. I enrolled in a Master’s Degree when we moved to Queensland. I planted a garden when we moved to Sydney. I volunteered when we moved to Adelaide. When we moved to Melbourne, I was already pregnant with my daughter, so new mothers became my community.

I don’t quite know when I started growing restless again. Partly, I think it had to do with having children. The day you hold that new baby in your arms, your world instantly unfolds like a meadow of night-blooming cereus: dazzling flowers, hypnotically-scented, and all opening en masse in one, magic night. But parenthood can also draw your world inside (like the night-blooming cereus closing at dawn, maybe?), and even if you don’t have kids, you’ve heard enough stories from friends and siblings and aunties and grandparents… or read enough mummy-blogs… that you don’t need me to talk about that odd and disorienting and beautiful and isolating parenthood bubble right now.

My point is that becoming a mother, while undeniably the best decision I ever made and the best thing I will ever do, also taught me to see my home-town in a different way. The exciting cafes and galleries and festivals and street-art and food trucks and pop-up events that once helped me fall in love with my city became, almost overnight, all-but lost to me, sitting at home with sleeping (or not-sleeping) babies while my husband worked 100 hours a week.

I have watched the world go on without me, from the distance of the Internet.

And when you take away all the wonderful things about life in the city, you start to notice the restrictive things. The lack of fresh air, open spaces, and trees. The reliance on other things (shops, cars, telephones) for even the most basic necessities of life. With a fidgeting toddler in one arm and a hungry baby in the other, the world feels as though it doesn’t belong to you any more, and for those of us used to being “in control” in the workplace, this new workplace feels about as out of control as workplaces come.

So, as I stood alone on that ancient hilltop in the breath-stealing wind, these were some of the thoughts that were going through my mind. I wanted to live in this place more than I’d wanted to live anywhere, ever. I sort-of cried, again, but I didn’t truly cry, because the wind stung my eyes and dried my tears before they could fall.

We won’t be moving to Cumbria any time soon, no matter how badly I want it. And the truth is that even more than I want that open-fielded life, I want to stay with the people who fill my life right now. They are my home, wherever I go (Home is wherever I’m with you).

After I climbed down from the castle ruins, I found my family in a little second-hand shop on the high street, deep in conversation with three locals who had each lived in this village and known one another for eight decades, or more. They recommended the fish and chips shop for lunch and, an hour or so later when we bustled in from the rain and found somewhere to sit, our new friends were already ensconced around a table at the back.

As we left, my husband secretly paid for their lunch and another round of their coffees, and it’s times like this that I remember why I first made him my home.

Tiny missives: 100 days in Dinan

It has been way too long since I hosted a postal project, but all that’s about to change.

Do you fancy receiving a tiny painting on a tiny vintage card, in the mail? I’m making 100 a day, starting this week, and would love to send one to you, my friend. Here’s the story…

Last month while we were in Paris, my family and I took a walk beside the river to browse les bouquinistes. You’ll have seen them I’m sure: the little green-box riverside markets that flank both banks of the Seine. They sell secondhand books and paper ephemera, and have been doing something similar, I believe, since as far back as the 16th Century.

We had left our village of Dinan the day before and I was looking for vintage postcards from the region, but then I saw these: tiny packets of photographs that tourists used to buy and carry home with them, from the days when cameras were rare and printing photographs was costly. Most of the packets were, I’m guessing, printed almost a hundred years ago, or at least some time between the first and second World Wars.

And as I turned them over in my hands, sniffed that old cardboard (is there anything better than “old book” smell?), I knew I wanted to give them life.

I’ve spoken in the past about how I believe postcards and other tourism souvenirs were made to travel and to be shared. The journey is the entire point of their creation. And yet so often, a postcard can sit unsent and unseen in a shoebox for years, or even decades. In 2017 my husband bought me a box of 1000 unused vintage postcards (most of them fabulously ugly), and I posted them to strangers and friends alike, all over the world, for the whole year. We called this the Thousand Postcard Project. A little while before that, we found some books of antique postcards and I sent those out too, then made miniature envelopes out of the tissue paper that separated them, and posted haikus into the world.

So as our little family all stood together in Paris, with the winter wind in our faces and the children moaning “Come on this is boring” because we were supposed to be en route to the Christmas markets, those tiny cards were calling to me and I couldn’t resist. I asked the bouquiniste, “How much for nine packets?”

Later, I wrapped the miniature postcards in a scarf and carefully stored them inside the heavy 18th-Century writing box I’d picked up at the flea markets in Dinan (which was in turn nestled inside my suitcase, wrapped in rain-coats and stuffed all around with socks to protect it from bumps and bashes, and which I carried around for an entire month while we travelled), and promptly forgot all about them. This made for a lovely surprise when we finally returned to Australia, and I began the arduous process of unpacking after five months away.

Since then I have been pondering what to do with them next, and today I have decided! I will use them as tiny touchstones that will link me back to the time I spent in our French village: to the small and precious moments we shared, and the little lessons (and big lessons) we learned.

The challenge: 100 days in Dinan

I have exactly 100 of these vintage or antique cards, each of them depicting a place or a moment from somewhere in France. So every day for 100 days I will take out a card and draw or paint something simple on it that illustrates our time in Dinan. (If you want to follow along on Instagram, I’ll hashtag #100daysinDinan whenever I share a picture).

It could be as grand as a castle or as simple as the tomatoes we picked up at the markets but, as I paint, I will be remembering the sunny day we visited that castle, or the way those tomatoes tasted, sliced onto baguette and sprinkled with salt.

Cumulatively, I hope the painting of these 100 cards will help take me back to Dinan in my heart, and help to keep alive some of the slow and precious lessons I learned during our time there.

The community: 100 tiny missives in the post

But that still isn’t setting the little cards free, is it. So the second part of this challenge is where you come in. Every day after painting a card, I will slip it into a handmade envelope and post it anywhere in the world.

Would you like one?

If you would, simply fill out the form below to share your address with me. This is all about community and for me these sorts of projects are sweeter for the sharing, so you don’t need to pay anything, join anything, sign anything or respond in any way. Just accept my thanks for being part of this little 100-day project.

The form will stay open until I have 100 addresses but, right now, I’m off to start painting!

UPDATE: I now have all 100 addresses so I’ve removed the form for this project. If you missed out, I’m sorry!

If you’d like to hear about my future projects first, you can subscribe to this blog using the box below, or subscribe to my monthly newsletter using this link. I also share what I’m doing on Instagram, and you can find me at @naomibulger.

The shocking moon

It hit me with a jolt at 9pm on a warm night last week. I’d closed up the hutch so the bunny could sleep for the night, and was outside in the garden having fed the cat and tucked her up in the tiny potting shed where she liked to sleep.

It was almost dark, the night air slightly cooler than usual and full of happy bugs buzzing around upon some urgent business or another. I could smell the daphne, and lavender where I’d brushed past it to feed the cat, and there was just the slightest hint of pink left in the quickly darkening sky. The first of the bats were crossing toward the park.

Everything was so very ordinary for a summer’s night at home, but it was the moon that shocked me. The feeblest, watery crescent, barely anything at all: just a line-drawing of a moon, really. I looked up at that line-drawing of the moon in the soft, pink sky and thought, “It will be a dark night tomorrow night” (no moon: safe for the hunted things)… and then I thought of the full moon I’d seen over water in Scotland, heavy and ripe and turgid, and the two seemed a world apart. Which, of course, they were: you don’t get a lot further apart than the winter solstice in the highlands of Scotland from the south of Australia in the heart of summer.

It felt like another lifetime in which I’d looked upon that pregnant Scottish moon, and that’s when the realisation struck me: it wasn’t another lifetime, it wasn’t even a month ago. I was looking at the same moon, still within the very same cycle. She had waned from full to crescent and, in much less time, I had circled our planet like a miniature moon, in human form.

Have the shadows on my face changed?

Am I thinner?

(When I was in labour with my daughter, it was long and difficult, and my husband and I cried at the end with the sheer magnitude of bringing her precious life into the world. When I was in labour with my son, it all went too fast: the labour, the birth, all of it. I felt I wasn’t ready and I couldn’t slow the world down enough to really feel the vastness of this little boy’s new life. Instead I had the nervous giggles - “Don’t worry, that’s pushing the baby out,” the midwife said - and my joyful child was born in ease and laughter, ready or not. I wonder if maybe air-travel is like this, sometimes.)

For thousands of years, we all travelled at the pace of the planet, no faster than legs could carry or horses could run or salty winds could blow. Journeys may have been long and arduous, sometimes boring and often dangerous, but through the weariness and the peril there was ample time to adjust.

To seasons, to people, to our own decisions.

Now, in the space of just 24 hours, we can journey literally poles from our departure point, to a place that is the same but opposite, in almost every way. And the change is so rapid that we just go with it: land passes in a flash beneath us without any time to take stock, we get the nervous giggles (or take a sleeping tablet) and, when we come-to, everything around us has transformed before we are ready.

Everything but the moon.

The moon, which waxes and wanes whether the sun burns cold or hot and which, tomorrow night, will make the world dark and safe for the hunted things.

Painting hacks (and it's ok if you're not doing it right)

Recently when I wrote my frequently asked questions post, I deliberately neglected to answer one of the questions I get asked the most often… “Can you teach me how to paint?”

The truth is that I have never felt confident enough to ‘teach’ painting, because in order to teach something it helps if you actually know what you are doing yourself! I am completely self-taught when it comes to my illustrations, and by “self taught” I mean I just keep painting, experimenting and practising… I haven’t read any books or watched any YouTube videos to improve my techniques.

(Although I’m actually hoping to remedy that this year, and take some formal lessons in botanical illustration at the Botanical Gardens in Melbourne, so maybe one day in the future I’ll have something more useful to share on here.)

But in the meantime, rather than teach you how to paint in any strict, best-practise or rules-based way, I am going to share some of the tips, tricks, hacks and techniques that I have stumbled across so far on my illustration journey.

Why it’s ok to not do it right

Because I’ve never received proper training, it is highly possible that the things I share are not the best way to do things, or that I’m simply “not doing it right.” And I think it’s important that we all seek ways to feel comfortable with this, when it comes to our own creative work.

“Not doing it right” is why I’ve held back on sharing too much in terms of how-to-paint content in the past (fear that I’m not doing it right, and fear that I’d therefore be teaching you to ALSO not do it right).

But now I’m thinking differently, and I’m going to call myself out on this defeatist attitude. Really, it’s just another form of “imposter syndrome,” the feeling most of us experience sometimes (or often) - especially when it comes to creativity - that we are not good enough, even when others appreciate our creations - and that any minute, the world will see us for the failures we secretly believe we really are.

Why do our brains do this to us?? This blog is not the place to explore the depths of human psychology (although I do talk a lot about imposter syndrome and the Inner Critic in my Create with Confidence course), but today I will stand up to my own Inner Critic and hopefully bolster you to stand up to your own, by sharing my perfectly-imperfect tips for watercolour painting.

My hope? That you will a) find some tips in here that are useful, but b) even if nothing here is useful, that you will feel empowered to experiment, play and create, without the constraints of “doing it right.” Just go for it!

Ok, shall we get started?

1. It’s ok to pencil first

You know those Instagram and YouTube videos in which people deftly put wet brushes to clean, white paper and in a matter of minutes create beautiful floral wreaths or sleepy cats on cosy couches, or potted succulents in greenhouses full of charm?

Yep, I can’t do that either.

I sketch my picture out using pencil first (2B because anything darker becomes harder to rub out later), then use waterproof black pens (my preferred brand is Sakura Pigma Micron) to draw it exactly the way I want it to look. Depending on what I’m wanting for the finished product, I add in more or less pen detail, and when that’s done, I rub out the pencil marks.

By the time I come to do the painting, it’s really not much more than colouring in.

2. Painting tools (otherwise known as “You can get your paints from the supermarket”)

My father always used to tell me “It’s a poor workman who blames his tools,” and this is as true in the art-room as it is in the workshop, garden or kitchen. To whit: great tools can make life a lot easier, but they are no substitute for elbow-grease and practise.

For many years, I used sets of watercolours and gouache paints picked up in a toy-store and supermarket respectively. From time to time I still dip into my kids’ Crayola paints, and have used them for all kinds of projects, including illustrations I’ve been paid to create. Until two years ago, I was still using the used gouache paint set my grandmother gave me when I was 10 years old.

In case you’re wondering which is which:

Watercolour paints are made by mixing colour-pigment with binder. The paint is applied by wetting it and then brushing it onto paper. Once the water dries, the binder fixes the pigment to the paper. Watercolours are super-versatile because you can make the colour stronger or weaker depending on how much water you use, and you can easily blend them together or layer them over each other in-situ (i.e. on the painting itself) to create almost any colour or shade you want

Gouache paints are very similar to watercolour paints, except that an extra white pigment (like chalk) is added, to make them brighter and more opaque. (Think Toulouse-Lautrec posters and you’ll know what gouache looks like). You can also blend gouache and watercolour with one another to create just the right colour or intensity you want

Even now, my “best” paints are really hobby-grade paints (I have Winsor & Newton watercolours in a set and Reeves gouache in tubes). I’m sure an upgrade would be a good thing, but I haven’t made the plunge so far and, if you’re starting out and don’t have the means or desire to invest just yet, don’t let that stop you: some decent brushes (my favourites are 'Expression' brushes by Daller-Rowney) and a good feel for colour-blending are all you need to create lovely paintings.

Which leads me to…

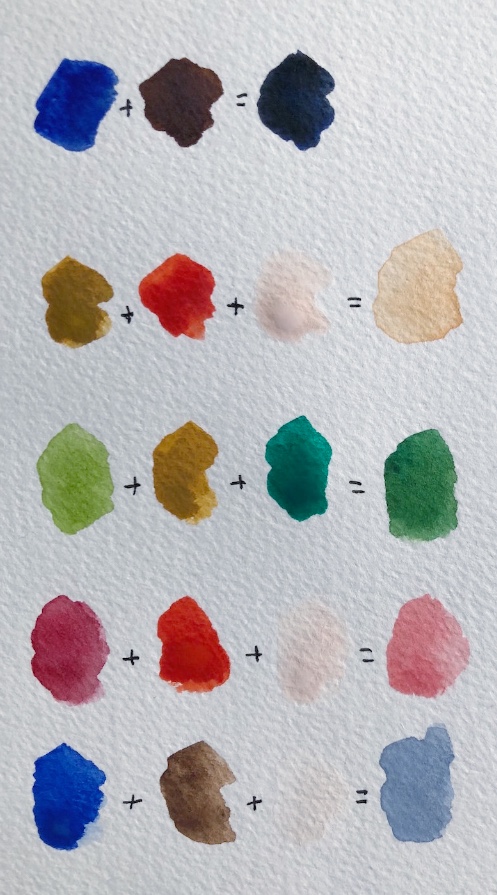

3. Colour-blending 101

Alright, most of us know that there are only three primary colours (colours you can’t mix from others): red, yellow and blue. With the help of black and white, you can realistically create all the colours, shades and tones you need with just these basics.

Luckily for us, most paint sets come with a lot more options, so when we are ‘blending’, it’s to create subtlety and more realism. This is how I blend my colours:

First, I get a non-porous palette on which to mix my colours. I have an old plastic paint palette that used to belong to my grandmother, but anything non-porous will do. I also use dinner-plates, the plastic lids of my paints, anything I have handy at the time

Onto that palette, I add a small amount of the first colour, either by adding a lot of water (via my brush) to a hard colour in a paint set, or by squeezing a tiny bit of that colour from a tube

Next, I add my second colour to the palette - nearby but not touching the first - in the same way. And so on for any subsequent colours. So for example if I was making purple, I’d do this with blue and red.

Now I’ll bring a tiny bit of one colour into the middle, and a tiny bit of the other colour into the middle, and mix them together. Based on what that looks like, I’ll add little bits more of one or the other colour, until it looks right. At this point if necessary, I might bring in some other tones, for example a bit of yellow to give it warmth, or white to brighten it up, or a tiny bit of black to tone it down.

The trick is to do all of this gradually, one small bit of colour at a time, so that you can rectify any mistakes or any time you’ve overdone it with one colour, and build up slowly until you get exactly the shade you want.

If necessary, I test my blends on a scrap piece of paper, just to see how they look once they dry, and also to test how much water to add, to create the look I’m going for.

Once I’m happy, I use this new colour on my painting. If I find I’m running out, I start the process all over again but make sure to do it before the original blend has run out, so that I can match the shade as closely as possible so that my painting remains consistent.

4. Colour-blending combinations that come in handy

While travelling for five months I had only the smallest of travel-paint sets, so I had to do a lot more blending to get the colours I like, than I do at home. I am drawn to a muted colour palette with soft, natural tones. But my little travel paint-kit was full of bright and primary colours. Here are some of my personal thoughts on colour, and some of my favourite combinations to achieve the tones I love.

First of all, I have something to say about black. I’ve learned from experience that black can easily dominate a watercolour picture. Look around you: most of the things you think on first impressions are black are not actually true black - most likely they are a kind of dark grey, or a warm kind of black or a cool kind of black… do you see what I mean? For this reason, I almost never use actual black in my paintings (other than in the ink outlines). Instead, I either water it down heavily until it becomes a kind of grey, or I use this blend in the top row…

TOP ROW: The “sort-of black” here is achieved by blending dark blue and dark brown together. If I want a warmer black I add more brown, if I want it cooler I add more blue. Because it’s not “true black,” it looks more natural on the page.

SECOND ROW: I mix light-brown, orange and white together with a fair bit of water to create this kind of neutral sand, which forms the base for all kinds of other colours I need. It goes well with greens, and is also a good starting point for skin-tones, as it can go lighter, darker, or a touch pinker

THIRD ROW: I paint a lot of botanicals, but find the ready-made greens are often unnatural. Also, there are just so many shades of green in nature, just one or two won’t cut it. Depending on what I have to hand, I most often mix a lighter green with a darker green, and then play with adding either light brown, yellow, or the sand I created in the second row above, to get the right tone for the leaf I’m painting.

FOURTH ROW: I’m not a fan of “candy pink” but I love a duskier pink in everything from flowers to sunsets to balls of knitting and an old lady’s hat. I get this by blending the dark red in my paint set with a kind of fire-engine red/orange also in the set, and then adding white until I get the exact depth I want.

BOTTOM ROW: The dove blue/grey here is one of my favourite colours, and I get it by mixing royal blue (as opposed to the dark blue of the top row) with dark brown, and white. It is a much prettier and more natural sky than just watered-down blue, and by adding a tiny bit more brown I can turn it into a lovely, soft grey, that is nice for animal fur, for example, or to add shading and texture to the bark of trees.

(NOT PICTURED BUT HANDY): Purple is quite difficult to make. Most of us know to blend blue with red, but too much red and you quickly get brown instead. I try going lighter first: I’d probably blend the dusky-pink and dove-blue colours in the bottom two rows together, to create a soft kind of lilac, then I’d add more of any of the colours in those two rows bit by bit, in order to get the exact tone I wanted. For me, this is easier than starting from scratch with just red and blue.

4. How to shade a painting

One of the easiest ways to bring a painting to life is to add shading. This not only makes whatever you’re painting look more three dimensional, it also adds interest and texture to what you have created. Imagine a painting of a cactus in a terra-cotta pot. You could simply paint the pot a terra-cotta kind of orange, OR you could create shading to help it look round, rough-to-touch, and give it that lovely aged patina that real terra-cotta gets.

Here are some of my tips and hacks for shading a painting:

A consistent light-source

The most important thing is to imagine a consistent light-source. Imagine shining a spotlight on whatever it is you are painting, or imagine which way the sun is shining or where the window is. Keep that light-source consistent in your entire pattern. It will do all kinds of weird things to people’s brains if the shadows on one part of your picture are on the left, and in the other part they are on the right. Light doesn’t do that (unless you’re a surrealist painter).

It’s lighter where the light is (duh, Naomi)

If the light is coming from the right, everything on the right-hand side of your picture (from terra-cotta pots to trees to animals to a bottle of wine) will be lighter and brighter on the right, and darker on the left. If the light is shining straight in front of your thing (like your terra-cotta pot), then it will be lighter and brighter in the middle, and get darker on either side. If the light is coming from directly above, the leaves at the top of your plant will probably be lighter than those at the bottom.

Shadows are not only about light and dark

Shadows don’t have to be created by simply applying lighter and darker versions of the same colour. Here are some of the ways that I create shadows in order suggest a light-source and create interest:

a) By using more or less intensity of the same colour (by adding more water to make it less intense)

b) By putting a watery drop of dark-blue, black or dark-grey into the areas that I want to shadow, after applying the first ‘main’ colour

c) By blending up two versions of a colour, one that is darker and/or more intense for the areas that are to be in shadow (for example in the case of a terra-cotta pot, I will often blend up two versions of the neutral ‘sand’ colour I shared above, one that has slightly more light brown in it, and another with a bit more pink. The first will be my main ‘in the light’ colour, and the second will be the darker shadows)

d) By using a completely different colour for the shadows, which might be unexpected but, because it is darker or stronger than the lighter areas, still tells viewers’ brains: “this is shadow.”

e) By painting the object one colour, and then “blotting away” the part I imagine to be in the sun, by pressing a paper-towel down over that part. Pressing the paper towel down immediately will remove all the colour. Instead, I like to wait a short while (a minute or thereabouts) and then press - that will take away some of the intense colour, but leave a softer version.

What ever technique you use to create shadows, if you want to have a soft or even invisible transition between the light and shade sections, a good tip is to take a clean, wet paintbrush and gently brush water over those “transition lines.” I don’t always bother with this because sometimes I like things to look a bit more rough and deliberate, but you can create a very natural, organic transition from light to shade if you want to, just using water in this way.

Here are some examples of different ways I’ve created shadows:

In this partial painting of a castle in Dinan, I used a watery dark blue to create the shadows, despite there not actually being any “blue shadows” on the golden stone walls

In this painting of a whale I made for a Boots Paper greeting card, I used a rather unnatural aqua blue as the shading at the bottom of his belly. The brightness of the blue, and contrast to the much more washed out almost-white of his body, creates the shade I wanted, while also suggesting a watery “whale in ocean” feel that I wanted, despite not painting the ocean

In this greenhouse mail-art picture, I used three different blends on the terra cotta pots to show the light, middle and dark sections of the pots (and to add interest and texture), and blotted some of the way almost entirely, then added white paint, in the areas I wanted to appear super-light. (Here is another picture of pots in which I was - slightly - more subtle in the shading)

5. Paper, and paper towels

Paper weight

(As in, the weight of the paper, not the old-fashioned paperweight that your grandfather kept on his desk).

In general, it is best to paint with watercolours and gouache on paper that has been specially made for that purpose. Watercolour paint is thicker than ordinary paper, which helps to stop it from going bumpy and buckling with all that water. So to give you an idea:

Ordinary copy-paper is usually 80gsm (gsm just stands for “grams per square metre” and refers to the weight, or thickness, of the paper)

A fairly average watercolour paper thickness is 185gsm

Obviously, you can experiment to see what works for you. I have used copy paper plenty of times in my mail-art, and just flatten it down under books overnight if it buckles too much.

But if you pop into an art supplies store and ask to buy watercolour paper, it can be a little overwhelming. There’s weight, there’s texture, and there’s all those different methods of making the paper itself. How do you choose?

Here’s what I have experienced so far (although please remember - see the top of this longgggg blog post - that I am an amateur):

Rough, textured watercolour paper looks fantastic on those old watercolour landscape paintings you might have seen. It gives a lovely tactile feel to the painting

If you want to paint something for printing (such as something for a book or stationery, like my illustrations for Boots Paper), the texture might go against you, because it will stand out too much against the smoothness of the page elsewhere

Paper that is “hot pressed” gives you that smooth feel I’m talking about, and the other benefit is that the paint dries quite quickly on it so you can layer your colours on quickly

Paper that is “cold pressed” tends to be slightly more textured (though not necessarily as rough as the old-fashioned paper I mentioned earlier) so the paint stays wet longer if you want to create some effects using water and blends. (As an example of this, take a look at the image of food around a grey dinner plate I shared earlier: the dinner plate was left blank because a logo was going to be added inside it, but for subtle interest, I used a lot of water to create that slightly ‘bleeding’ effect you see, reminiscent of glazed pottery)

Most watercolour paper is either cream or white - think about what you mostly like to paint when you choose, and the tones you prefer. For my Boots Paper illustrations I use a slightly more creamy background, because that is what Boots’ owner, Brenner, prefers. For my own work I like a brighter white, because I prefer cooler tones

Preparing the paper

Confession: I never do this. I mean never. I have never even tried it. However… best practise is probably to stretch and then tape down watercolour paper, to ensure you have a perfectly flat surface, and that the paper doesn’t buckle with all the water you apply.

Perhaps if I painted more landscape-style images with big wash areas, I’d have felt the need to learn how to prepare my paper sooner, and have cultivated this good habit. Because my illustrations are mostly quite small, it hasn’t been an issue (so far).

If you want to learn how to prepare your paper (or want to teach me), here’s a tutorial.

Paper towels

My favourite painting tool, other than paints, brushes and water, is a trusty paper towel. My favourites are the kinds that have little patterns embossed on them. I always have one or two paper towels beside me when I paint, and I use them to:

Clean brushes (after I’ve cleaned them in water, I wipe them off on paper towels to be sure they don’t have any paint residue left on them)

Blot away mistakes (if the paint is still wet, you can blot it with a paper towel and you are magically back to blank paper! Even if the paint has partly dried, try wetting it thoroughly with a brush, then blotting)

Blot sections of an image to create a feeling of light and shade, as I mentioned above

Create texture. If there are embossed patterns on the paper towel, it can be fun to actually use this in my painting: I press the paper towel over the paint while it is not quite dry (but not super wet or the paint will disappear) to create a fun, mottled pattern

Here is a short video in which I use a paper towel to create light and shade in my picture, let the paint partially dry (while I sip tea, naturally), then create a new layer in a different colour.

I hope this blog post was useful! I feel a little bit silly and vulnerable writing about “how to” on something I really do just muddle through, and feel about as far from being an expert as you can possibly imagine.

This lack of training probably makes me a fairly poor instructor: if there was something you were wanting to know from me about how I do my painting, but I’ve failed to mention it here, feel free to ask away. Likewise, if this actually is useful to you and you’d like to know more (such as some tips on drawing, for example, which in all honesty would be equally bumbled-through), let me know and I’ll see what I can come up with.

But no matter what, I DO hope this long post inspires you to pick up that dusty old paint-set (yes, the one you picked up for your kids at the supermarket) and wile away an afternoon playing with colour.

Still waters

How does the saying go? Still waters run deep,” if I recall. And, like most clichés, there is enough truth in the old, worn-out phrase to justify how the phrase wore out in the first place.

“Still waters run deep.” How things that appear to be still and quiet can actually hide passion and action, beneath the surface.

And, in my case, how taking the time to slow down and take stock has helped to bring me back to life and energy, from the brink of burnout.

As the year and our time abroad simultaneously draw to a close, I have been thinking about ways that I can apply the lessons I’ve learned during this quiet escape to the often noisy and busy life I lead in Melbourne. We can’t all live out our days in beautiful French villages, so how do we find rhythm and balance in what constitutes “ordinary life” for each of us?

I don’t feel that I have the answer yet, but I have learned some lessons that I hope to take with me into Australia in 2019. So I thought I’d share them today, partly because people have been asking me about how I’ll go adjusting when we return, and partly because maybe by telling you, I’ll feel that much more accountable to follow through.

This sabbatical was a precious gift, and I don’t want to let it drift away with the breeze.

* Saying no. I am going to say no a lot more. I will say it gently, and with love, and probably often with a twinge of sadness and FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). But I will say no, nevertheless, because saying yes has contributed to the feeling of overwhelm that threatened to drown these particular ‘still waters’ more than once in the past year.

* Eating well. It didn’t take an extended sojourn in France for me to learn that this was important, but it did take an extended stay for me to actually put this into practise. After we return, I want to eat at meal times and not snack in between. I won’t be too extreme in terms of limiting our diets, but I will do my best to make more of our meals rather than buying takeout, and to continue to challenge my children to try new things and embrace new flavours.

* Becoming my own benefactor. This is something I touch on, briefly, in my Create With Confidence course, but which I am also going to apply to myself this year. The idea is that rather than putting all the pressure on my art to earn my living (ie. “I want to create and I need to eat, and so I need to make money from the things I create”), I will be willing to do other non-creative things that earn a living, in order to fund the art I want to create. Part of this is because I am learning, slowly, that when I make art for money, I lose the love for the art. And I want to keep that love.

* Making for joy. By becoming my own benefactor, I also free myself up to create things purely for the joy of creating them. I’ve signed up for some workshops at the botanical gardens in January, learning to paint botanicals. I’m going to crate an illustrated almanac. I’ve fallen back in love with this blog (you may have noticed more frequent posts of late), because I’ve stopped writing for any reason other than for the joy of creating, and the desire to share my thoughts, ideas and questions, with you. I’ll launch that podcast. All of this feels exciting and genuinely freeing, because by earning my money in other places, I don’t have to find ways to make these ‘heart projects’ financially viable.

* Writing more letters. While in France, I have loved sinking back into the habit of writing long, chatty letters and making mail-art, purely for the joy of connecting with someone, or giving them joy.

* Escaping to nature. I am going to be deliberate about taking time out on weekends to escape into nature. Parks, forests, paddocks, orchards… trees are where I recharge, so I intend to be more proactive in seeking them out and losing myself among them. There will be picnics!

* Finding beauty. I live in the inner-city, and there is so much that I adore about where I live. But the truth is, I dream about a country escape, and I’ve realised I had subconsciously come to resent my home and its lack of open spaces. The same goes for my longing for a cooler climate. I truly detest the hot summer in Australia, and it always seems to last for such a long time. My goal, when I return, is to pretend to be a tourist in my own town. To imagine I am visiting for the first time, and in this way to fall back in love with the city I call home.

UPDATE: The evening after this blog post went live, I was listening to the Hashtag Authentic podcast with Sara Tasker, in which she chatted with Hannah Bulliant about “setting tingly goals for the new year.” I found myself shouting “YES” into my headphones while alone in the kitchen, and so much of their conversation resonated, for me, with the thoughts and ideas I’ve shared here. So if you’d like some further inspiration along the same lines (but much better articulated), take a listen to their episode, here.

A seasonal shift

The weekend before we left the village forever, they turned the Christmas lights on. I stepped out of our apartment in the twilight to go to the post office, and hadn’t taken two steps before the entire town burst back into light.

Christmas trees on every corner glowed with colour, rainbow twinkle lights floated in swathes above the cobblestones, intricate patterns of light made snowflakes above crossroads, and every laneway seemed touched with magic.

I raced back from the post office to call the family outside, and together we strolled through the wonderland, marvelling at each new discovery. It seemed as though almost the entire village had had the same idea, we were all, young and old, wandering the town in joy, and the streets were filled with the sounds of “Ooh!” and “Ahh!”, punctuated by church bells.

It felt like a fitting farewell to this town that we had called home for almost four months. From summer to winter, we watched the town transition from full bloom (and full to the brim) to a kind of turning-inwards, resting and readying for winter, and every new face on our town has been lovely.

In the summer, the streets hummed with tourists. The glacerie did a roaring trade, with towering coronets of triple-flavoured home-made ice creams, and markets filled with handicrafts lined the street underneath the ancient clock tower, every day. A horse and carriage clopped underneath our window every hour or so, and a miniature train carrying retired German tourists chugged over the cobblestones all day long.

We would wander down to the river in the sweltering heat, and sit on the stone edges with our feet in the water to cool off, or take a ride on the canal boat that took tourists to Lehon and back all day long (always telling the story, in two languages, of how if something happened to the horses pulling the canal-boats in the past, the captain’s wife would have to don a harness and drag that boat along the little river herself).

On Wednesdays, the square beneath our window, in front of the ancient basilica, would fill with stalls of antique toys and books and curios for sale. Scout wore a hand-woven “love knot” around her wrist, woven by a local woman at the market. Ralph found a red tin van that had once held chocolates. I picked up a 300-year-old writing desk, and a hand-painted ceramic kugelhopf mould from a famous artists in Alsace.

Everything in Dinan was alive. The geraniums in the pots outside our windows burst into extravagant colour, and the dancing light seemed to filter inside, even before dawn. There were jazz concerts in the square below us, sending music into our living room through the open windows until after midnight, while we ate crackers and cheese and sipped rosé, and I painted the memories of our grand adventure.

And then the wind turned cold.

As the seasons changed, so did the village. The glacerie closed its shutters for the last time in the year, as did our favourite boulanger, and many of the shops and restaurants taped handwritten signs to their closed shutters: fermé jusqu'en décembre (closed until December).

It was a lot easier to move around the town without the crowds, and the children never had to wait for a space on the tourniquet in the playground, and the cafes and bistros that did remain open started selling vin chaud (hot wine).

The breeze picked up, and the trees changed colour. Gold dominated, but there was also brown, orange, and crimson in the mix. On windy days, the sky would rain colour. We collected conkers and walnuts, and roasted found chestnuts. The chemin des pommiers (apple path) below the castle walls was slick with fallen, rotting apples, a picturesque death-trap to any who ventured down that steep slope.

I walked the children to childcare in the golden glare of sunrise, and home again in the dark. On days off, we started frequenting a deli where the paninis were particularly good, and the proprietress was super-friendly towards the children. In fact, everyone grew friendlier, now that the throngs and crowds had melted away.

And then one dark afternoon, they turned the Christmas lights on.