JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

Old things

Time is such an arbitrary concept, isn’t it. I mean, I understand the way we measure time, with the passing of the sun and the turning of our planet. But our experiences of time are as varied as we are.

Like when new parents discover, “The days are long but the years are short.” It’s so true, but how does that work? Or, do you remember how the summer holidays used to stretch out when you were little, so long that you could barely remember the person you were at the start of the holidays, and no matter how you filled them, you were absolutely and completely ready to go back to school by the time they were done? And how now, that same period of time - six weeks in my case - seems to pass before you can blink?

And, why do we look on other people’s times through rose-tinted glasses? We are Gil in Midnight in Paris, a man of our time who longs for (and comes to experience) the Paris of the 1920s, the artistic heyday of Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and Picasso. Or are we Adriana from the same movie? A woman already living Gil’s dream life, yet yearning for another era altogether, La Belle Epoque, when Tolouse Lautruec, Paul Cézanne and Vincent Van Gogh were changing the face of art for their contemporaries.

My husband and I like to binge-watch historical dramas on Netflix. They evoke both the romance and brutality of another time - we are transported to the dawn of the Viking era, the court of Genghis Khan, Tudor England, the American Civil War, or Birmingham after WWI (and apparently everyone throughout history was extremely good looking, and had excellent teeth).

Last year, deep in a covid-lockdown winter, I gently and quietly passed a milestone birthday. My family had planned some BIG celebrations, all of which had to be cancelled due to the lockdowns. I wasn’t sad (well, only sad for my husband who had gone to so much trouble on my behalf): for my introverted soul, not having a big party in my honour was more of a relief than a loss.

But that didn’t mean I wanted to ignore the birthday, to deny the passing of time. Birthdays, and especially milestone birthdays, can herald in new eras. In the months that have passed since my birthday, I have caught myself slowly, softly, changing. It hasn’t been conscious or deliberate, but more of a gentle embracing of what this new time in my life means. What it means to my health, my habits, and how I see “the future” now that I’ve probably already lived for more years than I have yet to live (boy isn’t that something to think about!).

I’m always drawn to old things, and old places. I like that old things hold stories, stories that began before me and hopefully will outlive me. I want to live in old houses, I like to visit old towns and cities. I like holding old things in my hands, even if they are simple, everyday objects like spoons or books. I sniff the pages of old books and think, “I wonder how many other people have been lost in the worlds of these pages, just like me?” Even better if there’s an inscription in the front of the old book, or notes in the margins.

And now it dawns upon me that I am becoming an “old thing.” And I like it! I don’t feel the need to compete with youth, as I once did, to try and stop time. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not ready for the zimmer-frame yet: part of embracing this new-old me is to accept new ways to take care of my body and mind. But I’m totally ok with watching Father Brown and Antiques Roadshow, and admitting this to you.

All of these thoughts tumbled around my mind as I wandered through the lovely old town of Chiltern yesterday, clutching a grocery-bag of cheese, crackers and mandarins to sustain the family on the final leg of our journey from Canberra to Melbourne.

I like old things. So I’m learning to like old-me.

Follow the sun

Did you know that there is a word in the English language specifically to describe a person who loves flowers? It’s anthophile.

At the end of last year, our neighbour planted a row of sunflowers at the front of his house, that he had raised from last year’s seeds. He planted them in pure compost, and they shot skyward within weeks. Every morning they all look to the right and watch the sunrise, slowly turning their heads, straight-backed, as the day passes, to salute the sunset.

The summer heat these past few weeks has been searing, but my neighbour’s sunflowers don’t seem to mind. The sun wilts me, but they soak it in and beam it back to us with a wink and a grin. There is a school at the end of our street and the sunflowers have become locally famous, children and their parents stopping to admire them on their walks to and from school. Mothers like to cup their hands around the flower-heads - as big as bread plates - while bees harvest pollen until they are so drunk and heavy they can barely fly.

Yesterday we followed the sun and a dusty dirt road to a paddock on a hill beside an ice-cream van and a barely-there dam. Growing on the hill were hundreds, thousands, possibly millions of sunflowers. Nobody was counting. The hill was swathed in gold and green, and peppered with families in sensible shoes carrying secateurs, and Instagrammers in gingham sundresses carrying selfie-sticks.

We picked seven stems to give to a friend, but then we stopped for lunch at a pub on the way home, and the traffic was terrible so we had to take Scout straight to her horse-riding lesson, and by the time we finally made it home those sunflowers looked about as good as you’d expect after spending six hours in the boot of a hot car, without water.

I popped the sunflowers into a jar instead, set inside an old urn by the window, and they transformed my home in the south of Australia into somewhere old and elegant (but still slightly shabby) in the south of France. Two ladybirds climbed over their stems, and sunlight tickled their crushed and bruised petals.

We all sat on the floor playing UNO (I am now the Bulger Family champion, thanks to a the-dealer-didn’t-shuffle-properly hand of four wild-cards and a yellow 2+), Scout still in her riding jodhpurs, as the light danced and played over that flower-filled window, slowly sinking and deepening, until it was time to take the children upstairs.

Vincent van Gogh didn’t only paint sunflowers in a ceramic vase. In one painting, one of my favourites, they rest on a table, the cut ends of the stems staring out at us while the petals gently wither, folding inwards from age. Old and dying flowers have a broken-things beauty of their own, a decaying loveliness we could all probably embrace, if we were braver than we are.

Van Gogh planned, once, to paint a dozen panels of sunflowers in preparation for Paul Gaugin’s visit. “A symphony of blue and yellow,” he wrote to his brother. He was painting sunflowers in 1888, three years after the house I’m living in was built. I wonder if the original owners of this house ever brought stems of these big, bright, furry favourites home to brighten the same window where mine shine as I sit and type. Did the first owners of this house know, then, that a sad and tortured man was painting sunflowers in Arles, France? Or that he would one day become one of the most lauded and beloved artists in history?

And why is yellow the colour of joy and madness and sickness? Who makes this stuff up?

Stories of a house

Do you remember the house in the Pixar movie Up? And the way love and happiness and big dreams (and sometimes even sorrow) filled that house for many, many years, soaked into its walls, and made it a home, so profoundly so that the old man refused to give it up, no matter the personal cost?

My house looks a little bit like that house: it’s more than 100 years old with a big sash-window at the front resting on a bluestone sill, patterned bricks, a shingle roof, and a sweet chimney right in the middle. There’s a coloured window over the front door - a door we painted bright red because the colour brings us joy - iron lacework over the verandah, and a chair that we like to sit on in the evenings to watch the goings-on in our pretty street*.

After 12 years, two babies and a lot of laughter, my house feels a bit like the Up-house, too.

But now we are leaving it. It’s time for our family to move on to new places - up, up and away, just like the movie, except that unlike the grumpy old man in Up, we can’t bring our beloved house with us. And even though I know it is the right decision for my family, it is still breaking my heart a little bit.

Don’t be fooled by the white paint: the walls of this house are thick with stories, like layer upon layer of beautiful wallpaper. A hundred years of families have lived and loved in here, and I think you can feel them.

We read a story on the internet once - I wish I could find it to link to it now - of two sons who once lived in this house, leaving it to join the fight in the Great War. We imagined them opening the front gate (the very same front gate that we still walk through now - did it creak then, too, I wonder?) and striding down Canning Street - even back then a beautiful boulevard with Victorian-era palm trees - and out into the terrible turmoil of war. We imagined their mother, lump in throat, waving from the window of the same sunny front bedroom that I now use as my office and art studio.

Only one son returned.

Here’s another story of the house:

Once upon a time a man and a woman fell in love from opposite sides of the world. The woman lived in New York while the man lived in Australia, and together, they decided to buy a house. The man found somewhere suitable in Melbourne, a city the woman had only ever visited twice, and only briefly. The woman agreed to give all the money she had inherited from her grandmother to her new boyfriend, to pay the deposit on a house she’d never seen, in a city she barely knew.

It was crazy and all her friends told her it was crazy and you know who I’m talking about, don’t you.

I still remember the auction to buy that house. It was Saturday morning in Melbourne, which meant it was Friday night in New York, humid and just growing dark. I’d been out at a wine bar with a friend but I jumped in a taxi and raced home early so I could listen to the action on my ‘phone. My stomach was churning with nerves and excitement. That was all my savings. The money I’d planned to use to buy a studio apartment in New York, and I was trusting it to someone I’d known for the shortest of times, tying me back to Australia.

The auction was a moment of profound trust - trust in the man I’d so quickly fallen in love with, and trust in my own instincts (which, thankfully, proved well-founded). So the house became a symbol of our love, and my faith in our love.

This was the house where we finally created a home, after six international and interstate moves in 18 months.

It was the home we brought baby Ralph into, and Scout was so small when we came here that she doesn’t remember anywhere else. We gave them the sunniest bedroom just off the master, with city views over rooftops, that - in our pre-kid days - we had imagined would become a reading-and-painting room.

The dining table beside the big, arched window has hosted countless meals with beloved friends, lunches that have turned into dinners and the roar of laughter that has echoed late into the night.

We’ve had rousing sing-alongs around the piano in the family room, camped out on blow-up mattresses in front of the open fire in the lounge room, started a book club, run a small business, managed to blow up the microwave on Christmas Eve one year, then managed to blow up the oven on Christmas Eve on another year (whoever moves here next will be the happy recipient of my new, self-cleaning oven, lucky them!), and no matter how hard life has been from time to time, I don’t think a day has gone by without laughter.

The garden (sleeping now for winter but always bountiful in spring and summer) became a loving respite during lockdown last year, a secret, walled garden filled with roses, apple trees, Japanese maples, hydrangeas, and a pomegranate - as well as foxgloves, cosmos, gaura, poppies, clematis and nigella in summer; where we could lie in the sun and feel part of the earth outside. On sunny, pre-covid days, the garden was the scene of spring parties, impromptu picnics, and one time, a fully-fledged Christmas concert.

And now we are saying goodbye to this house, where we have been so very happy. I truly believe that the next people who live here will feel a little something of that happiness, because we all know bricks retain heat, and I hope that joy will filter into their own lives, too. It will be a happy place for them to live, don’t you think?

So the stories of this house will continue and even though they won’t be our stories to tell, any more, our family still has a place somewhere in the fabric that tale. Or at least I hope so.

* Canning Street is divided by a big median-strip of grass through the middle, dotted with palm and poplar trees that were planted almost a hundred years ago. It’s the most wonderful place for community to happen. Here are some of the things we’ve watched, while sitting on the bench on our front verandah:

- picnics

- yard sales

- formal dinner parties

- an inflatable swimming pool

- a man practising how to cast a fishing line

- movie nights (with bedsheets for screens)

- table tennis

- and even once, a big brass band

ps. The photographs on this blog post (other than the summer garden and Scout floating up and away) are from the official listing for our house, which you can see here if you’re curious like me and like to sticky-beak into other people’s houses (or if you happen to know someone LOVELY who wants to buy a much-loved house on Canning Street).

Summer dreams

There was a moment while we were walking along the closed-off streets, and a band of teenaged buskers played Riders on the Storm across the way. We hustled from shade-patch to shade-patch, sunburn stinging our thighs despite having left the beach by ten in the morning.

Ralph’s hand was sweating in mine as he told me all about the water-soaker he’d just blown $6.95 of his pocket-money on at the pharmacy. The stream of information seemed endless: I learned all about the intricacies of high-tech material that had gone into the making of it (plastic, foam), the hydraulics that enabled it to both suck and spurt water, the additional equipment required for maximum impact (a beach, or failing that a bucket), and the extraordinarily complex battle-plan that would, no doubt, ensure him victory in the battle against his sister on the morrow.

I had a moment while we walked together and Ralph talked, my head dizzy with the heat, when it felt as though I was somewhere else, outside myself, watching our little family tableau like a movie.

I was me of 20 years ago, passively watching a middle-aged mother and her child winding in and out of beachside shops on a summer holiday. The little boy was carrying a water-soaker and chatting non-stop, almost drowning out the squeak of his flip-flops, and all the sounds merged with the chatter of a hundred other holiday-makers, shop jingles in open doors, distant waves, and Riders on the Storm which had blurred and distorted into something else by The Doors that I couldn’t quite remember.

The scene was still happening, Ralph was still talking, but the me of 20 years ago couldn’t identify with any of this. It didn’t belong to her, it was somebody else’s son and they were living somebody else’s life.

I thought, “How is this even me?” Because I’m still me of 20 years ago, every bit as much as I’m me of today, and I can’t seem to make them fit together. So different are these two women, their lives, their choices… opposite, almost. And yet I was happy 20 years ago, and I am happy today. How does that work?

We found a bakery and bought vanilla slices because vanilla slices are the best things on earth and we are on holidays and anyway, the diet starts tomorrow. The vanilla slice brought me back into my body which was bad timing, because Ralph chose that moment to open a bottle of fizzy water and it exploded all over all of us, so my body definitely felt that. On the other hand, the day was so hot that nobody minded being wet.

*. * *

I can hear cicadas in the bottle-brush trees outside. Piercing, they sing in unison, their chorus ebbing and flowing like ocean waves and never fully receding. There is sand all over the kitchen floor and flip flops strewn from one end of the room to the other, where the puppy has picked them up, one at a time, and discarded them. I know I should probably clean up but I sip water instead and open my computer to write, because these are the last days of the summer holidays, and I’m not time-travelling any more. I’m mindful - so mindful - that I’m here and now.

And in 20 more years, when I’m outside tending the apple trees on the tiny farm I hope I’ll own by then and suddenly and unexpectedly float back to the me of January 2021, I want to remember exactly what it felt like.

Welcome to market

Holly!* (Because it’s Christmas, after all).

Slowly I am painting my way through the seasons, in an attempt to reconnect with the root of the matter when it comes to life on this earth-and-water ball of ours spinning through space, which we call home. My goal is to create a kind of illustrated perennial almanac, a diary that celebrates the seasons and becomes a guidebook for living seasonally, even in the city, via gardens, farmers markets, the wilds and the kitchen.

This is a personal project, something I’m doing for myself because I want to learn, but hopefully (if I do it right) it might be useful or inspirational for others, too. With that in mind, I’m sending my ‘almanac’ out into the world, one glorious, seasonal produce at a time, and that’s what I want to tell you about today.

I called this project “A Year at the Market” but in reality, it has been more than two years in the making. The seeds of this idea came while I was living with my children in Dinan, a rural village in France. Shopping in our village was done the traditional way, at the farmers markets each Thursday morning. Here, people from the entire village - and all the outlying villages - would come to buy all the fresh vegetables, fruit, cheese, meat, fish and eggs they needed for the week to come.

I learned to arrive early to get my hands on the freshest produce, (although this came with its own set of hazards because all the French grandmothers likewise got to the markets early, and nobody wants to come between a French grandmother and the best looking leek on the table).

At first, navigating the markets was as confusing as it was frustrating. I’d arrive clutching a shopping list in my fist, all the ingredients for all the meals I’d hoped to cook that week, and make my way in a somewhat haphazard fashion from stall to stall, searching for everything I needed. Only to realise half way into my shop that a third of the ingredients on my list were not in season, and another third were not even grown in this region.

(One week, after the children and I had been collecting chestnuts, I tried to buy Brussels sprouts so that we could pan-fry them together with the chestnuts and some local bacon. When I asked one of the farmers if they had sprouts, she said, “they’re not in season… not for two weeks!” I realised that the food available at the market didn’t change season-by-season, it literally changed week-by-week.)

As the weeks and months went by, I learned that pre-planned menus and shopping lists were all-but useless. If I wanted to shop locally and eat seasonally (and I did), I’d have to learn to accept whatever happened to be available at the farmers market on each particular week, and build a week’s worth of family menus from the best and freshest food I could find.

The problem was that I’m not a naturally confident cook, and certainly didn’t have a ready-made repertoire of meals and recipes that could be planned on the fly, depending on whether tomatoes were good this week, or mussels, or romanesco broccoli, or spring lamb.

I found myself wishing there was some kind of field guide that could help me navigate the seasonal markets, in the moment. Not a recipe book to look up when I got home, but one that could tell me - while I was at the market - how to choose the best of the produce I was looking at, what to expect from it, what to cook with it (so I could plan my meals while I shopped), and what to do with it if I happened to buy too much, and couldn’t eat it all in time.

When I couldn’t find the kind of field guide I was looking for, the idea began to bloom in my mind to create one myself and that, finally (after two years!) is what I’ve done.

I’ve written a pocket-sized guide to shopping seasonally and navigating the farmers markets with confidence, called Welcome to Market, and am in the process of researching, writing and illustrating a new “Farmers Market Field Guide” to complement Welcome to Market, every month. Each new Field Guide celebrates one particular fruit or vegetable, lovingly illustrated in the botanical style of the holly and asparagus you see here, and tells a full story, from when it’s in season, how to choose the best, and what to do with it.

The whole project is called ‘A Year at the Market’ and I’m super excited and inspired by the idea, which is why I’m sharing this story with you today.

If you’d like to come on this journey with me, I’ve created a subscription service through which you can receive a host of seasonal shopping resources, as well as a new Field Guide every month. I’ve kept the price very low - basically it’s what it costs me to produce it (not including my time, which is yours for free) - because this is not a business venture, but something I’m incredibly passionate about, and want to share with likeminded people.

In all honesty, I’m probably tapping into my childhood. When we were little, our local supermarket began selling an encyclopaedia series, month by month. We weren’t a family that could afford the classic Encyclopaedia Brittanica, so, instead, we would purchase a new volume of the supermarket encyclopaedia every month. Over time, we built up a wonderful resource that saw me through almost a decade of school projects on everything from wool to marine biology to a history of electricity, and we gained a sense of achievement as each red-spited issue was released by the supermarket and added to our bookshelf.

I want to create the same sense of value and curation for you, by posting a new Field Guide to you every month.

There are three things I’d love to know from you, if you have the time (if you received this post via email, just click the title or “view original post” to see it on a website and a comment box will be available):

If you have a preserving recipe that you absolutely swear by, I’d love to hear it. I’m testing recipes for my field guides because I want to provide people with ways to use all that wonderful produce if they buy too much at the farmers market, or have a glut in their own garden

Have you come across a fruit or veggie at the shops or the market and you really wish you knew more about it, and what to do with. it? Let me know in the comments here. I’m hoping to cover just about everything over time, but I’ll prioritise requests

If you’d like to join me for A Year at the Market, there’s more information about this 12-month subscription (and all the lovely gifts I’ll personally post to you) in my shop, here. The first issue will be posted mid-to-late January, but there’s also a printable gift certificate if you want to give this subscription to someone as a thoughtful Christmas gift

*ps. I painted this sprig of holly at beginning of winter where I live in Melbourne. Snow season started the same weekend, and holly was sending out bright red berry-beacons of cheer on neighbourhood hedges everywhere. Near our apartment in Dinan, France, there was a famous Victorian-era holly tree with variegated leaves, just like this one. Holly berries are poisonous, but ancient herbalist Culpepper says the leaves and bark are good to heal broken bones (not that I’ll be trying either any time soon).

Christmas in a time of Covid

After one of the most difficult years most of us can remember, I think we could all do with a little moment to stop and celebrate, don’t you? This online magazine - a bumper version of my monthly newsletter - contains ideas for celebrating and sharing the joys of Christmas, even if you are in lockdown; mindful gift ideas and DIY projects; tips for writing Christmas letters; 12 festive envelope templates for you to colour in and post; and loads more.

Flip through the magazine below (if you hover over the magazine window you’ll see an option to make it full screen), or click “download” to print and read it the old-fashioned way, and to use any of the resources and templates inside. (Give it time if it’s slow to download - it’s a big file!)

Can you hear the garden singing?

When the world closed back in March, and the us of our familiar communities, neighbourhoods and even entire nations was reduced to the surprising smallness of the we, or me, that inhabited each of our individual homes, Nature welcomed us like a mother hen.

We tended seedlings on window-sills, pruned back overblown autumn branches, and finally learned how to pronounce the names of our house plants. (It’s Monstera Deliciosa, not Monsteria). I would rest my palms on the soil beneath the Japanese maple tree, fingers outspread, and imagine the way the soil connected me to the trees and through them the root systems and through those root systems all the other root systems that spread across my yard and my neighbourhood and beyond the closed borders, all of us belonging to one giant ecosystem, even while we were apart.

At night I would look up at the moon and imagine all the other people alone in their houses, looking up at that same moon.

(Outside our tiny lockdown worlds, Nature didn’t weaken her embrace. Ducks swam in the Trevi Fountain. A herd of wild goats wandered through a Welsh town. The skies above some of the world’s most polluted cities shone clean and clear.)

Nature, and in particular for many people their gardens, became a place of solace. Even more so than usual. For me and my children, our tiny garden became the one place where we could go outside for as long as we wanted to. When the weather was warm we’d carry their schoolbooks into the garden and read on the grass. We’d eat out there when we could, and together tend to the plants: pruning the roses, netting the fruit trees to protect them from marauding possums, and planting rows of tiny carrot seedlings, celery, and Brussels sprouts.

Now spring is here and though my garden was late to bloom this season, it is well and truly making up for lost time now, showering us with an abundance of colour and perfume. For a little while I congratulated myself on a gardening job inadvertently well done, until I began to notice the roses blooming in front gardens and over fences and along road-edges, all over my city.

Nature is having a moment.

I don’t know if it is the extra love and attention, the cleaner air and water, a sign of resilience after last year’s climate disaster, or something altogether different, but right now, it seems to me that the gardens of Melbourne are singing.

I shared this thought on Instagram recently and was surprised by the sheer number of people - not just in Melbourne but all over Australia and the world - who are noticing the same thing.

There is such sweet solace in a garden. Even in the tiniest of gardens, just a pretty pot with one happy houseplant growing, changing, reaching up and out - ever toward the light - and I have never been more grateful for my little pocket of green-and-rainbow than I am right now.

Can you hear the gardens singing?

It's just a carrot

Except of course it was never going to be “just a carrot.”

Last weekend when our Premier announced that hairdressers could start working again, my husband booked a haircut for the very next day. “It’s symbolic,” he joked. “My curly hair is a symbol of our oppression.” I laughed at him, but I could also relate. Here in Melbourne we have been locked up for so long that everyone is starting to lose perspective, and the little things can feel very big indeed.

My husband has out-of-control hair. I have shingles. My kids are most probably illiterate.

And we are the lucky ones: we have steady incomes, we have each other, and we have our health (although just between us, shingles suck).

Not long ago I bought a take-away coffee from a cafe around the corner from our house, and the owner started to cry. She said, “I don’t know what I’ll do if we’re not allowed to open soon. I haven’t been able to pay my rent for seven months, and I’ve put everything I have into this business. I’m in my 60s and I live alone. What else am I going to do?” She said that if her landlord insisted she pay the missed rent she’d be sleeping “out there,” and gestured to a park bench, still wrapped in “Do not cross” tape because we were not supposed to sit down in public places.

For my part, ever since our second-wave lockdowns tightened in July, I began nursing a fantasy of going out for a walk, and not stopping. Not stopping when my one hour outside allowance was up. Not stopping when I reached the five-kilometre line that we were not supposed to cross. Not even stopping after the nightly 8pm curfew. In my imagination I just kept on walking, and strangers spoke of me as “that crazy, middle-aged lady who is walking her way around the world.” Kind of like Forrest Gump (except that I wanted to walk, not run, because I’m not that crazy).

I almost called this blog post “Run, Forrest!”

I ordered carrot seeds from the Diggers Club back during the first lockdown in March and, when they arrived about two months later (since everyone else seemed to have had the same idea at the same time), I popped them into soil in old egg cartons, and hoped they’d germinate.

Those baby carrots had to survive the entire winter outside in the ground, having their feathery tops battered by winds and munched by marauding possums, overcrowding one another because I didn’t bother to separate the seeds the way I was supposed to, and being generally neglected as my every waking hour was consumed by fitting overdue work commitments in around school-at-home for two children, while indulging fantasies of going for a walk and not stopping.

Yesterday I pulled the carrots out of the ground to make room for snapdragons (priorities, my friend!). Most of them were still small, many of them curly or split in two or twined around each other like lovers. But a few were long and straight like this one here. The children said, “Those look like they come from a shop!” in awed tones, as though this was the highest of possible achievements.

If my husband’s hair is symbolic of our oppression, my carrots are symbolic of our resilience. We can grow, even when the conditions are not… quite… ideal. And we might not all be big and strong: some of us feel very small. Some of us feel split, or wonky, or twisted. But we can still grow, and we still have the capacity to nurture and nourish each other.

The news isn’t looking great here, and the optimism we ventured to feel a week or two ago that things might open up quickly is starting to fade before it even had a chance to bloom, but tomorrow I’m going to make a Sunday roast. I’ll sauté the carrots (straight ones, baby ones and curly-wurly ones all) in butter and orange and honey. And when I serve them up I’ll tell my family they are not just carrots. They are a reminder of our capacity to survive, and grow.

A body of work

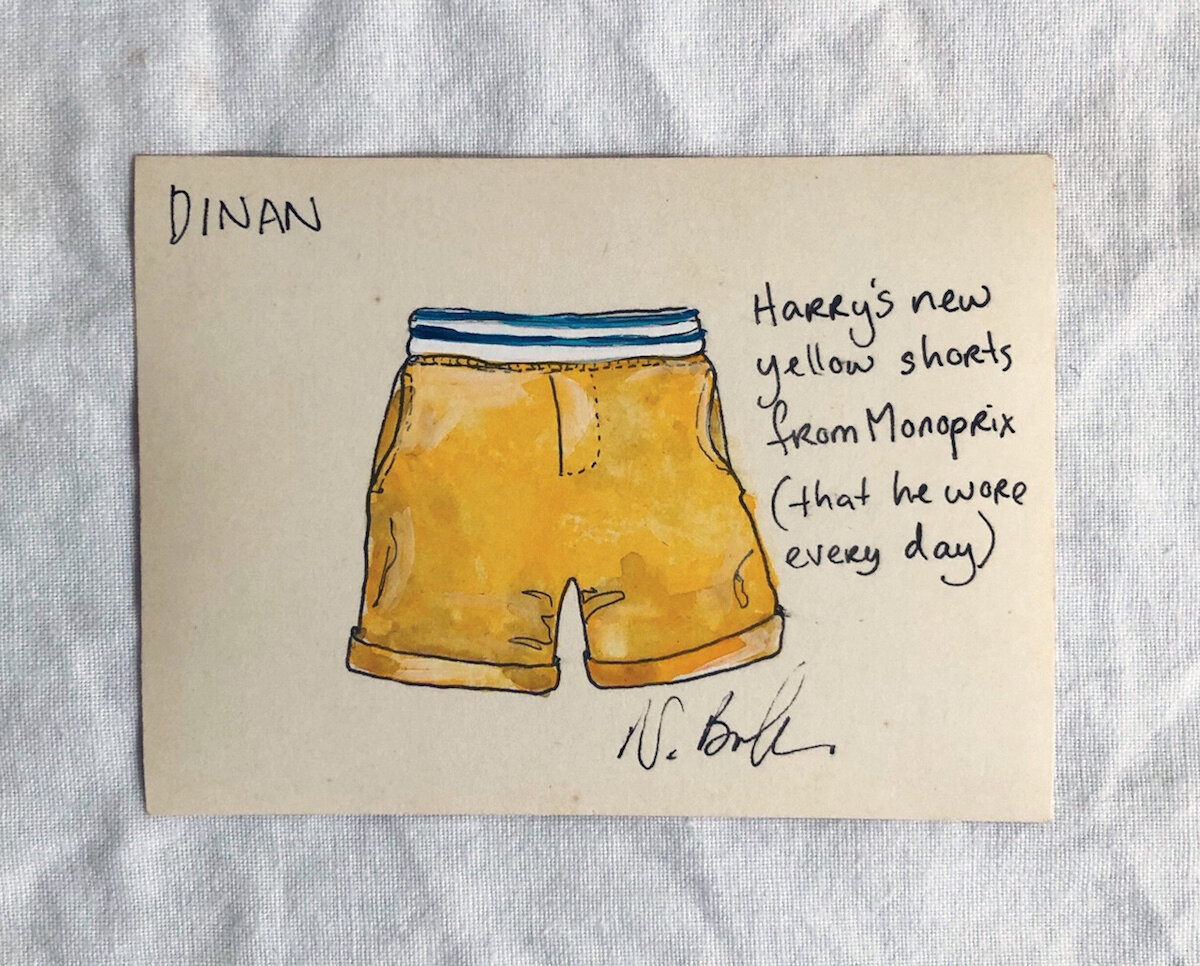

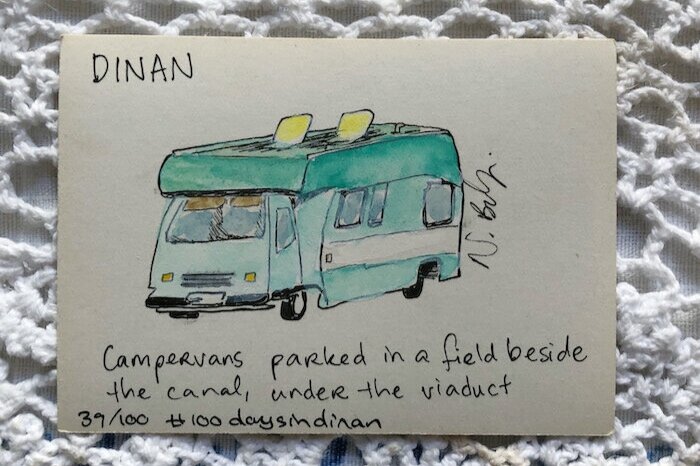

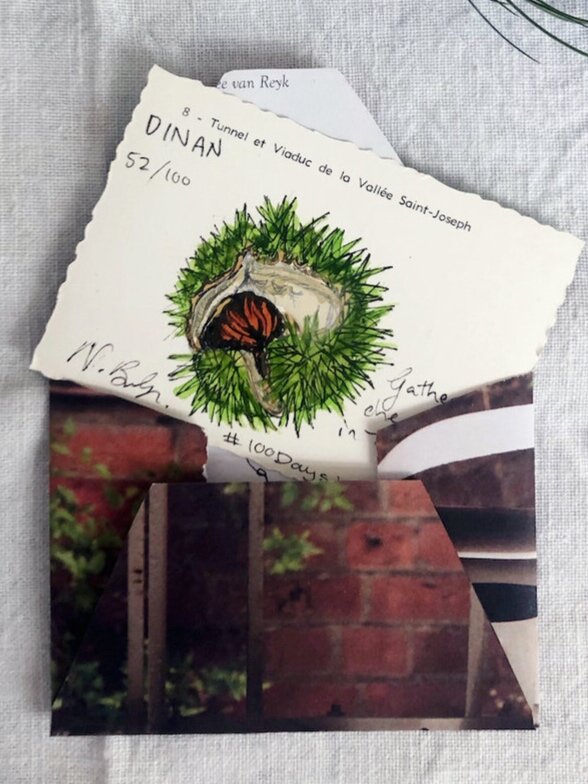

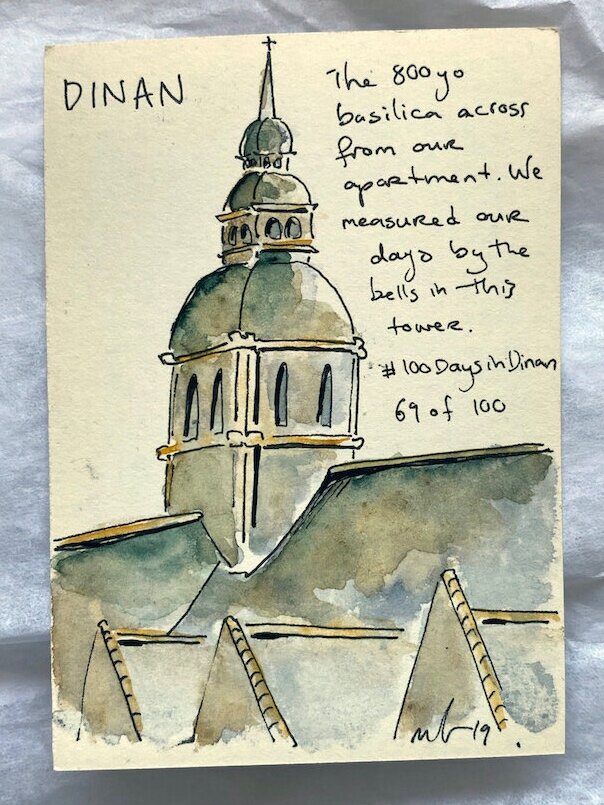

I called this project #100DaysInDinan. One hundred days can feel as fleeting as a week if you happen to be on sabbatical in a medieval French village with your two children. One hundred days pass in the blink of an eye as you watch those children grow (why are their pants too short again? weren’t they in nappies just yesterday?). Although I’m sure you’ll agree one hundred days can stretch out like a lifetime during lockdown.

When I set myself the challenge of illustrating and posting a miniature postcard every day for a hundred days, I hoped to celebrate the memories of our hundred days in France and make them last a little longer. I also wanted to see if I could establish some kind of creative habit that would last me beyond the project.

In the former, I was very successful. Each miniature illustration took me back to a place, a moment, or a conversation: tiny touchstones that helped to keep me connected with those halcyon days. But in the latter, I have to say I was an abject failure. I still wholeheartedly subscribe to the premise of “doing something creative for 20 minutes a day,” which is where I was going when I set myself this challenge. But the reality is that it took me a lot more than 20 minutes - sometimes several hours - to plan out, draw, paint, annotate and sign each postcard, then trace, cut out and paste together a mini envelope, then look up the next person’s address on my list of a hundred addresses and carefully write their address onto a tiny piece of paper and glue it to the envelope, then look up the postage cost online for the destination country and find the right stamps, then affix a wax seal to the back…

Frequently I struggle to find 20 minutes in my day so multiple hours was just too big an ask. That, and of course I’d have to pack away all my paints and papers every time anyone wanted to eat at the dining table (unreasonable family!), only to bring them all out and set up again the next time I wanted to paint. The reality then of my “one painting a day” project was that I’d knock out seven or eight in a weekend by doing nothing else, and then not get to the rest for another month or two. And so time passed.

I sent the last of the postcards to their new homes during Melbourne’s second lockdown, more than a year after I’d started my “100 days” project. The postal services being what they are at the moment, some of them are even taking 100 days or more to complete their journeys across the world. But I kind of like that. It’s fitting, in its own way, that a project that meant so much to me and was such an unexpectedly enormous labour of love would then take its own sweet time to complete the journey. After all, the postcards I was using were 100 years old or more: they had waited a century to be posted, there was no need to rush to the finish line.

And yet as I slipped the final 12 postcards into the red letterbox outside the post office, I did so with a distinct feeling of underwhelm. All that time. All that work! All those precious memories. All those oceans for my postcards to cross. And I was left with… nothing. Just the empty cardboard packets in which the postcards had been stored, locked away for a hundred years or more in somebody’s drawer.

It occurred to me too late that I had actually created for myself a “body of work.” But by posting them all away one by one, I hadn’t let the pleasant weight of creating that work actually settle.

I had been mindfully in the moment, painting each postcard one at a time, reliving the memory it evoked. But moments in life, while individually precious, are also cumulative, each of them drawing on those that came before and forming the scaffold for those that are yet come. (If you look at it this way, a life is a body of work. Or many bodies of work, to be more accurate.)

My miniature paintings were each part of a larger work, tiles in a mosaic, and while I wasn’t necessarily thinking about them in this way as I painted, the idea must have been there somewhere in my subconscious because instinctively I numbered each of them, solidifying their individual places within the one-hundred. They were never meant to exist on their own, and I learned that truth too late. If I had my time again I’d hold the postcards back, painting them all and then viewing them together to see what kinds of stories they told, before posting them back out into the world.

So now, for you but if I’m honest mostly for myself, I am going to retrospectively survey my body of work.

By pulling all 100 illustrated postcards together in this gigantic blog post, using iPhone photographs I snapped before posting (sometimes quite hastily), I have tried to piece together what this body of work might have been. Doing it this way has felt a little bit like an archaeological dig through my memories, once again painstakingly focusing on each individual item, not seeing the big picture until it is finally done, then standing up at last, stretching my back, and surveying the landscape uncovered.

Here it is, my body of work. A hundred days in the living, a year and a half in the making, and for these postcards, a century in the waiting. I wonder what stories it has to tell, when all the pieces are connected together like this? What does it say to me? Where does it take you?

If I learn the answer I’ll let you know.

Meadow-flowers and sneaky seed-bombs

The week before we left France, I caught up with our friend Rachel, who had been helping the children and I learn French. The children were at Ecole Maternelle that day so it was just me and Rachel. The air was December-cold despite the patchy sun so we sat indoors, at a table by the window, and ordered our coffees.

It was our goodbye: the children’s dad was arriving in a matter of days and then we would all cross the channel for our Christmas holiday in England and Scotland but today, in my final French lesson, Rachel and I wanted to talk about things closer to home. Like the bread vending machine that had been set up in a neighbouring town, because there are laws in France around bread always being available, and the local boulanger had closed down. So the council had a vending machine installed and the bakers from the town next door would stock it every morning with freshly baked baguettes and croissants. Ah, France.

And guerrilla gardening, we talked about guerrilla gardening. Rachel was part of a gardening group in her town that took on the responsibility for beautifying the public areas with green and growing things and, before we said goodbye, she handed me a little packet of seeds. It was a mix of wildflowers that could take root and grow in the tiniest of spaces, the little cracks and grooves between paving, and along the sides of walls. Rachel’s group had been handing these seed packets out for free to residents in their little town, encouraging everyone to scatter them as they walked to encourage diversity and discourage weeds, so now she did the same to me.

I carried the seed-packet home with me and I have been imagining myself as some kind of “meadow-flower Johnny Appleseed” ever since, skipping through Melbourne scattering wildflower-seeds wherever I go, turning my inner-city suburb into a bejewelled field of flowers.

But there are strict biosecurity rules in Australia and so I have never had the courage to open that little packet of seeds. It sits in the 18th Century writing desk I also brought home from France, among other mementoes I hold precious from that time, and has instead inspired home-grown wildflower melanges.

The company behind the seed packet Rachel gave me has been specialising in growing and harvesting meadow flowers for more than 70 years, and they sell mixtures of seeds for every imaginable use. Wildflowers that can be mown over; wildflowers that attract bees; wildflowers that change throughout the seasons. Wildflowers that grow in poor soil; wildflowers for cemeteries; wildflowers for damp and boggy earth. Tall wildflowers, small wildflowers, wildflowers in colours that suggest a medieval carpet (I’m not kidding), and on it goes. Hello, magical occupation envy!

So I have decided to create some wildflower mixes of my own, using seeds safely grown here in Australia. Lacking any handy meadow-space anywhere nearby to create glorious fields of flowers en masse, I’ve gone with “seed bombs” instead, and that’s what I really wanted to share with you in this blog post.

Seed bombs, or seed balls, are simply little balls of clay, compost and seeds, rolled up and left to harden and dry. They are a guerrilla gardener’s best friend because you can just drop these little balls wherever you want your seeds to grow: they’ll sit there innocently until the next proper, soaking rain falls, allowing them to germinate and take root, helped by the tiny starter-soil you’ve given them with the clay and compost.

If you’d like to try making seed bombs, my method is below, along with the “wildflower seed recipe” I created (for medium-height wildflowers that grow well together in spring and summer in a meadow setting, many of them chosen to enrich the soil and encourage pollinators).

If you’ve ever made and shared seed bombs before - or if you give it a try after reading this blog post - I’d love to know how you get on!

Wildflower seed bombs

Wildflower meadow mix

Assorted poppies

Cornflowers

Silene pink

False Queen Anne’s Lace

Chocolate Queen Anne’s Lace

Love-in-a-mist

Flax

Coriander

Alfalfa

Buckwheat

Seed bomb recipe

Equal parts of clay (I used modelling clay from the local art supplies store), and

Compost (I used “zoo poo”)

A handful of vermiculite, a natural mineral that fosters plant growth

Your mix of wildflower seeds (or see mine, left)

Method

In a bucket, soak the clay in some water to soften it and make a mushy, easy-to-manipulate, muddy gloop

Add in the compost and vermiculite and mix them all around with your hands until everything blends together

Sprinkle the seeds over the top, and stir them in with your hands

Now roll your clay/compost/seed mix up into little balls about the size of ping-pong balls, and set them aside to dry

When you are ready, start spreading the floral joy!

ps. The wildflower meadow pictured here was at Hever Castle in Kent, UK. The children and I spent an afternoon there (can you spot Ralph, then aged four, racing through the flowers in the photograph above?) and it was every bit as heavenly as you’d imagine it to be.